The "You Are What You Eat" Customer Segmentation

This project uses k-means clustering to segment up a grocery chain’s customer base in order to increase understanding of shopping behavior, and thereby enhance the relevancy of targeted messaging & customer communications.

Table of contents

Project Overview

Context

ABC Grocery would like to understand who is buying what at their stores. They wonder if lifestyle choices may affect which food areas customers are shopping into, or more interestingly, not shopping into.

The overall goal here is give ABC Grocery a better understanding of their customers by segmenting them based on the food categories that they typically buy, thus allowing the business to make informed advertising and customer communications decisions.

Fortunately, we have data on the categories of food that customers buy, and we can employ an unsupervised Machine Learning algorithm - k-means Clustering - to distinguish types of ABC’s customers by the groceries that they buy.

Actions

After compiling the necessary data from tables in the database, I use the Pandas package in Python to aggregate transaction data across product areas from the most recent six months to a customer level. The final data for clustering is, for each customer, the percentage of sales allocated to each product area.

After preparing the data, other k-means cluster analysis tasks include:

- Feature Scaling: data first needs to be standardized so that the measured distances are on the same scale for each variable.

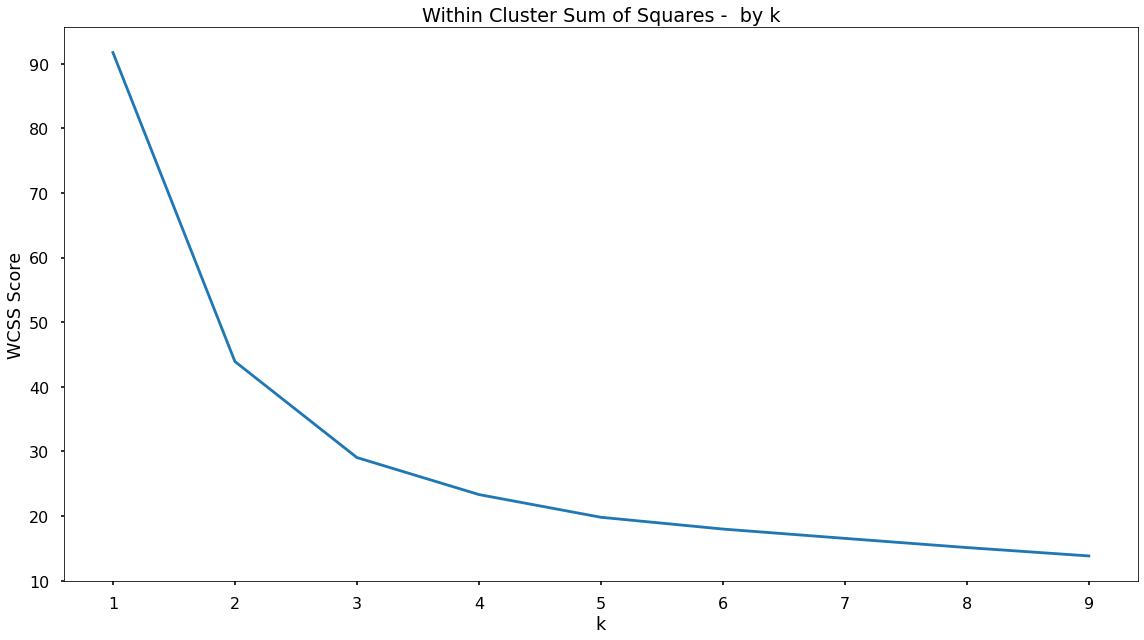

- Find k segments, using Within Cluster Sum of Squares for unsupervised learning tasks.

- Apply the k-means algorithm onto the product area data.

- Append the clusters to our customer base and then profile the resulting customer segments to understand what the differentiating factors were.

Results

WCSS analysis suggests customers should be segmented into 3 clusters. These clusters ranged in size, with Cluster 0 accounting for 73.6% of the customer base, Cluster 2 accounting for 14.6%, and Cluster 1 accounting for 11.8%.

These categories yeilded interesting insights!

For Cluster 0 we saw a significant portion of spend being allocated to each of the product areas - showing customers without any particular dietary preference.

For Cluster 1 we saw quite high proportions of spend being allocated to Fruit & Vegetables, but very little to the Dairy & Meat product areas. It could be hypothesized that these customers are following a vegan diet.

Finally customers in Cluster 2 spent significant portions within Dairy, Fruit & Vegetables, but very little in the Meat product area - so similarly, we would make an early hypothesis that these customers are more along the lines of those following a vegetarian diet.

To help embed this segmentation into the business, let’s call this the “You Are What You Eat” segmentation.

Growth/Next Steps

It would be interesting to also run this segmentation task at a lower level of product areas, so rather than just the four areas of Meat, Dairy, Fruit, Vegetables - clustering spend across the sub-categories below (or within) those categories would mean we could create more specific clusters and get an even more granular understanding of dietary preferences within the customer base.

Although I only include in this analysis the variables that are linked directly to sales - it would interesting to also include customer metrics such as distance to store, gender, etc. to give a even more nuanced understanding of customer segmentation.

It may also be useful to test other clustering approaches such as hierarchical clustering or DBSCAN to compare the results.

Data Overview

ABC Grocery does sell more than just food items, but for the sake of this analysis, they are only looking to discover segments of customers based upon their transactions within food based product areas, so we will need to only select data from those.

In the code below, I process the data as follows:

- Import the required python packages & libraries

- Import the tables from the database

- Merge the tables to tag on product_area_name which only exists in the product_areas table

- Drop the non-food categories

- Aggregate the sales data for each product area, at customer level

- Pivot the data to get it into the right format for clustering

- Change the values from raw dollars, into a percentage of spend for each customer (to ensure each customer is comparable)

# import required Python packages

from sklearn.cluster import KMeans

from sklearn.preprocessing import MinMaxScaler

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# import tables from database

transactions = pd.read_excel("data/grocery_database.xlsx", sheet_name = "transactions")

product_areas = pd.read_excel("data/grocery_database.xlsx", sheet_name = "product_areas")

# merge product_area_name on

transactions = pd.merge(transactions, product_areas, how = "inner", on = "product_area_id")

# drop the non-food category

transactions.drop(transactions[transactions["product_area_name"] == "Non-Food"].index, inplace = True)

# aggregate sales at customer level (by product area)

transaction_summary = transactions.groupby(["customer_id", "product_area_name"])["sales_cost"].sum().reset_index()

# Convenient table for interpretation, but our modeling data will come from the pivot table below

# pivot data to place product areas as columns

transaction_summary_pivot = transactions.pivot_table(index = "customer_id",

columns = "product_area_name",

values = "sales_cost",

aggfunc = "sum",

fill_value = 0,

margins = True,

margins_name = "Total").rename_axis(None,axis = 1)

# transform sales into % sales

transaction_summary_pivot = transaction_summary_pivot.div(transaction_summary_pivot["Total"], axis = 0)

# drop the "total" column as we don't need that for clustering

data_for_clustering = transaction_summary_pivot.drop(["Total"], axis = 1)

After preprocessing using Pandas, the dataset for clustering looks like the below sample:

| customer_id | dairy | fruit | meat | vegetables |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0.246 | 0.198 | 0.394 | 0.162 |

| 3 | 0.142 | 0.233 | 0.528 | 0.097 |

| 4 | 0.341 | 0.245 | 0.272 | 0.142 |

| 5 | 0.213 | 0.250 | 0.430 | 0.107 |

| 6 | 0.180 | 0.178 | 0.546 | 0.095 |

| 7 | 0.000 | 0.517 | 0.000 | 0.483 |

The data is at the customer level, and the columns represent each of the food product areas. Within each of those we have the percentage of sales that each customer allocated to that product area over the past six months.

K-Means

Concept Overview

K-Means is an unsupervised learning algorithm, meaning that it does not look to predict known labels or values, but instead looks to isolate patterns within unlabelled data.

The algorithm works by partitioning data-points into distinct groups (clusters) based upon their similarity to each other.

This similarity is based on the distance (in this case, eucliedean, or straight-line distance) between data-points in n-dimensional space. Each variable that is included lies on one of the dimensions in space.

The number of distinct groups (clusters) is determined by the value that is set for “k”.

The algorithm does this by iterating over four key steps:

- It selects “k” random points in space (or, centroids)

- It then assigns each of the data points to the nearest centroid (based upon euclidean distance)

- It then repositions the centroids to the mean dimension values of it’s cluster

- It then reassigns each data-point to the nearest centroid

Steps 3 & 4 continue to iterate until no data-points are reassigned to a closer centroid. In doing so, the centroids, which began as random points, end up centered within distinct groups (or clusters) of data.

Data Preprocessing

There are three vital preprocessing steps for k-means:

- Dealing with missing values

- Dealing with outliers

- Feature Scaling

Missing Values

Missing values can cause issues for k-means, as the algorithm won’t know where to plot those data-points along the dimension where the value is not present.

Fortunately, in this case we don’t have to worry about imputing the missing values or removing those rows because we aggregated our data for each customer.

Outliers

Outliers can cause problems for k-means clustering tasks. Even though we will scale the data, an outlier at one extreme of a distribution can cause the more normal values to be “bunched up,” far from the outlier, and this will make it hard to compare their values to the other input variables. But in this case our data is percentages, so this won’t be a problem.

Feature Scaling

Normalization, rather than standardization, is the feature scaling method of choice for k-means tasks. Normalization rescales datapoints so that they exist in a range between 0 and 1.

As our data are percentages, they are already spread between 0 and 1, but we still have to normalize to make sure those spreads are proportionate between variables. If one of the product areas makes up a large proportion of customer sales, for example, this may end up dominating the clustering space. When we normalize, even product areas that make up smaller volumes will be spread proportionately between 0 and 1!

The code below uses the MinMaxScaler functionality from scikit-learn to normalization our variables. The new data frame object (here called data_for_clustering_scaled) is the one that will actually be used in the model. The unscaled data frame (data_for_clustering) will be reserved for later profiling and interpretation, as this will make more intuitive business sense.

# create our scaler object

scale_norm = MinMaxScaler()

# normalize the data

data_for_clustering_scaled = pd.DataFrame(scale_norm.fit_transform(data_for_clustering), columns = data_for_clustering.columns)

Finding A Good Value For k

At this point, the data is ready for the k-means clustering algorithm. Before that, however, we need to know how many clusters we want the data split into.

For unsupervised learning tasks there is no right or wrong value for this. It migth depend on the data, which may be naturaly clustered in particular ways, or it may depend on the business questions at hand. For ABC Grocery, we’re in an exploratory stage of understanding customer segments, so it may be best to follow the data, or aiming for a simple/small number of clusters. From there, future analysis can be used to extract more nuanced segmentation.

By default, the k-means algorithm within scikit-learn will uses k = 8, meaning that it will look to split the data into eight distinct clusters. But there is a way to actually ask the data, at what point does adding clusters result in diminishing returns.

The Within Cluster Sum of Squares (WCSS) approach to deriving k measures the sum of the squared (euclidean) distances that data points lie from their closest centroid. In the code below we will test multiple values for k, and plot how this WCSS metric changes. As the value for k increases (in other words, as we increase the number or centroids or clusters) the WCSS value will always decrease. However, these decreases will get smaller and smaller each time we add another centroid and we are looking for a point where this decrease is quite prominent before this point of diminishing returns.

# set up range for search, and empty list to append wcss scores to

k_values = list(range(1,10))

wcss_list = []

# loop through each possible value of k, fit to the data, append the wcss score

for k in k_values:

kmeans = KMeans(n_clusters = k, random_state = 42)

kmeans.fit(data_for_clustering_scaled)

wcss_list.append(kmeans.inertia_) # WCSS is also referred to as inertia

And then we can visualize the results to find a balance point were segmentation is maximized and diminishing returns are minimized.

# plot wcss by k

plt.plot(k_values, wcss_list)

plt.title("Within Cluster Sum of Squares - by k")

plt.xlabel("k")

plt.ylabel("WCSS Score")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Based upon the shape of the above plot - there does appear to be an elbow at k = 3. Prior to that there is a significant drop in the WCSS score, but following the decreases are much smaller, meaning this could be a point that suggests adding more clusters will provide little extra benefit in separating our data. A small number of clusters can be beneficial when considering how easy it is for the business to focus on, and understand, each - so we will continue on, and fit our k-means clustering solution with k = 3.

Model Fitting

The below code will instantiate our k-means object using a value for k equal to 3. We then fit this object to our scaled dataset to separate our data into three distinct segments or clusters.

# instantiate our k-means object

kmeans = KMeans(n_clusters = 3, random_state = 42)

# fit to our data

kmeans.fit(data_for_clustering_scaled)

<br

Append Clusters To Customers

With the k-means algorithm fitted to the data, we can now append those clusters to our original dataset, meaning that each customer will be tagged with the cluster number that they most closely fit into based upon their sales data over each product area.

In the code below we tag this cluster number onto our original dataframe.

# add cluster labels to our original data

data_for_clustering["cluster"] = kmeans.labels_

Cluster Profiling

Once ther data is separated into distinct clusters, we can refer back to our percentages table to find out what it is that is driving the separation. Then ABC Grocery can understand the customers within each, and the behaviors that make them unique.

Cluster Sizes

First, let’s assess the number of customers that fall into each cluster.

# check cluster sizes

data_for_clustering["cluster"].value_counts(normalize=True)

Running that code shows us that the three clusters are different in size, with the following proportions:

- Cluster 0: 73.6% of customers

- Cluster 2: 14.6% of customers

- Cluster 1: 11.8% of customers

Based on these results, it does appear we do have a skew toward Cluster 0 with Cluster 1 & Cluster 2 being proportionally smaller. This isn’t right or wrong, it is simply showing up pockets of the customer base that are exhibiting different behaviors - and this is exactly what we want.

Cluster Attributes

Second, let’s see how these distinct groups actually shop.

# profile clusters (mean % sales for each product area)

cluster_summary = data_for_clustering.groupby("cluster")[["Dairy","Fruit","Meat","Vegetables"]].mean().reset_index()

That code results in the following table…

| Cluster | Dairy | Fruit | Meat | Vegetables |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 22.1% | 26.5% | 37.7% | 13.8% |

| 1 | 0.2% | 63.8% | 0.4% | 35.6% |

| 2 | 36.4% | 39.4% | 2.9% | 21.3% |

For Cluster 0 we see roughly even portions being allocated to each of the product areas, with meat being the highest portion of their grocery spend. For Cluster 1 we see quite high proportions of spend being allocated to Fruit & Vegetables, but very little to the Dairy & Meat product areas. It could be hypothesized that these customers are following a vegan diet. Finally customers in Cluster 2 spend, on average, significant portions within Dairy, Fruit & Vegetables, but very little in the Meat product area - so similarly, we would make an early hypothesis that these customers are more along the lines of those following a vegetarian diet - interesting!

Application

Even though this is a simple solution, based upon high level product areas it will help leaders in the business, and category managers gain a clearer understanding of the customer base.

Tracking these clusters over time would allow the client to more quickly react to dietary trends, and adjust their messaging and inventory accordingly.

Based upon these clusters, the client will be able to target customers more accurately - promoting products & discounts to customers that are truly relevant to them - overall enabling a more customer focused communication strategy.

Growth & Next Steps

It would be interesting to run this clustering/segmentation at a lower level of product areas, so rather than just the four areas of Meat, Dairy, Fruit, Vegetables - clustering spend across the sub-categories below those categories. This would mean we could create more specific clusters, and get an even more granular understanding of dietary preferences within the customer base. This might be especially useful for Cluster 0 above, which contains nearly 3 out of every 4 customers.

Here we’ve just focused on variables that are linked directly to sales - it could be interesting to also include customer metrics such as distance to store, gender etc to give a even more well-rounded customer segmentation. For example, critical business questions might include: Are certain types of customers only coming to ABC for meat, or for produce?

It might also be useful to test other clustering approaches such as hierarchical clustering or DBSCAN to compare the results.