Predicting Customer Loyalty Using ML

This project applies machine learning regression models to predict customer loyalty scores for a subset of customers for a hypothetical client, ABC grocery. ABC Grocery has loyalty scores - the percent of grocery spend at ABC vs. competetors - for only half of its clientelle. Here I use and compare predictive power of OLS multiple regression, Decision Tree, and Random Forest models to estimate the remaining scores based on other customer metrics, such as distance from store, total spent, number of items purchased, and more.

Table of contents

- 00. Project Overview

- 01. Data Overview

- 02. Modelling Overview

- 03. Linear Regression

- 04. Decision Tree

- 05. Random Forest

- 06. Modelling Summary

- 07. Predicting Missing Loyalty Scores

- 08. Growth & Next Steps

Project Overview

Context

ABC Grocery hired a market research consultancy to get market level customer loyalty information for their customer database, but the researchers could only tag about half of ABC’s clients.

The overall goal here is to accurately predict the loyalty scores for the remaning customers, enabling ABC grocery a clear understanding of true customer loyalty for more accurate and relevant customer tracking, targeting, and communications.

Because we have data on other customer information, such as their distance to the store, the types of groceries they buy, how much they spend, etc. we can use this data to train and assess a regression model that predicts the loyalty scores we already have, and we use that model to infer the remaining scores.

Actions

After cleaning and processing the data, including subsetting the customers for whom we need to predict scores, I test three regression modeling approaches, namely:

- OLS Multiple Linear Regression

- Decision Tree

- Random Forest

Results

For each model, I assessed predictive accuracy (proportion of variance explained) and cross-validation. The Random Forest model had the highest predictive accuracy and the highest (four-fold) cross validation metrics.

Metric 1: Adjusted R-Squared (Test Set)

- Random Forest = 0.955

- Decision Tree = 0.886

- Linear Regression = 0.754

Metric 2: R-Squared (K-Fold Cross Validation, k = 4)

- Random Forest = 0.925

- Decision Tree = 0.871

- Linear Regression = 0.853

As the most important outcome for this project was predictive accuracy, rather than understanding the drivers of loyalty, Random Forest is the model of choice for making predictions on the customers who are missing the loyalty score metric.

Growth/Next Steps

Although other modelling approaches could be tested (e.g., XGBoost, LightGBM) to see if even more predictive accuracy could be gained, our model already performs well. More value may now come from understanding the nature of the key features of our model. For example, a cursory analysis suggests that a customer’s distance from the store is the strongest predictor of their loyalty, so we might seek to collect data on the direction of that distance to better understand loyalty in relation to nearby competitors.

Key Definition

The loyalty score metric measures the % of grocery spend (market level) that each customer allocates to the client vs. all of the competitors.

Example 1: Customer X has a total grocery spend of $100 and all of this is spent with our client. Customer X has a loyalty score of 1.0

Example 2: Customer Y has a total grocery spend of $200 but only 20% is spent with our client. The remaining 80% is spend with competitors. Customer Y has a customer loyalty score of 0.2

Data Overview

This loyalty_score metric exists (for half of the customer base) in the loyalty_scores table of the client database.

The key independent variables will come from other client database tables, namely the transactions table, the customer_details table, and the product_areas table.

Using pandas in Python, we merged these tables together for all customers, creating a single dataset that we can use for modelling.

# import required packages

import pandas as pd

import pickle

# import required data tables

loyalty_scores = pd.read_excel("data/grocery_database.xlsx", sheet_name = "loyalty_scores")

customer_details = pd.read_excel("data/grocery_database.xlsx", sheet_name = "customer_details")

transactions = pd.read_excel("data/grocery_database.xlsx", sheet_name = "transactions")

# merge loyalty score data and customer details data at customer level

data_for_regression = pd.merge(customer_details, loyalty_scores, how = "left", on = "customer_id")

# transactions data are input at the level of product area (e.g., vegetables, dairy) for each transactions, so they need to be aggregated to the level of customer_id.

sales_summary = transactions.groupby("customer_id").agg({"sales_cost" : "sum",

"num_items" : "sum",

"transaction_id" : "nunique",

"product_area_id" : "nunique"}).reset_index()

# rename aggregated columns for clarity

sales_summary.columns = ["customer_id", "total_sales", "total_items", "transaction_count", "product_area_count"]

# engineer an average basket value column for each customer

sales_summary["average_basket_value"] = sales_summary["total_sales"] / sales_summary["transaction_count"]

# merge the sales summary with the overall customer data

data_for_regression = pd.merge(data_for_regression, sales_summary, how = "inner", on = "customer_id")

# split out data for modelling (loyalty score is present)

regression_modelling = data_for_regression.loc[data_for_regression["customer_loyalty_score"].notna()]

# split out data for scoring post-modelling (loyalty score is missing)

regression_scoring = data_for_regression.loc[data_for_regression["customer_loyalty_score"].isna()]

# for scoring set, drop the loyalty score column (as it is blank/redundant)

regression_scoring.drop(["customer_loyalty_score"], axis = 1, inplace = True)

# save our datasets for future use

pickle.dump(regression_modelling, open("data/customer_loyalty_modelling.p", "wb"))

pickle.dump(regression_scoring, open("data/customer_loyalty_scoring.p", "wb"))

After this data pre-processing in Python, we have a dataset for modelling that contains the following fields…

| Variable Name | Variable Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| loyalty_score | Dependent | The % of total grocery spend that each customer allocates to ABC Grocery vs. competitors |

| distance_from_store | Independent | “The distance in miles from the customers home address, and the store” |

| gender | Independent | The gender provided by the customer |

| credit_score | Independent | The customers most recent credit score |

| total_sales | Independent | Total spend by the customer in ABC Grocery within the latest 6 months |

| total_items | Independent | Total products purchased by the customer in ABC Grocery within the latest 6 months |

| transaction_count | Independent | Total unique transactions made by the customer in ABC Grocery within the latest 6 months |

| product_area_count | Independent | The number of product areas within ABC Grocery the customers has shopped into within the latest 6 months |

| average_basket_value | Independent | The average spend per transaction for the customer in ABC Grocery within the latest 6 months |

Modelling Overview

If there is a model that accuractly predicts loyalty scores for the customers that have that data, then we can use that model to predict the customer loyalty score for the customers that do not.

In supervised machine learning form, the data can be randomly subset into a training set and a test set. Then we can train and test our OLS Mulitple Linear model, Decision Tree, and Random Forest models.

___

Linear Regression

The scikit-learn library within Python contains all the functionality we need for each of these, incluing Linear Regression. The code sections below are broken up into 4 key sections:

- Data Import

- Data Preprocessing

- Model Training

- Performance Assessment

Data Import

Since we saved our modelling data as a pickle file, we import it. We ensure we remove the id column, and we also ensure our data is shuffled.

# import required packages

import pandas as pd

import pickle

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

from sklearn.utils import shuffle

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split, cross_val_score, KFold

from sklearn.metrics import r2_score

from sklearn.preprocessing import OneHotEncoder

from sklearn.feature_selection import RFECV

# import modelling data

data_for_model = pickle.load(open("data/customer_loyalty_modelling.p", "rb"))

# drop uneccessary columns

data_for_model.drop("customer_id", axis = 1, inplace = True)

# shuffle data

data_for_model = shuffle(data_for_model, random_state = 42)

Data Preprocessing

For Linear Regression, certain data preprocessing steps need to be addressed, including:

- Missing values in the data

- The effect of outliers

- Encoding categorical variables to numeric form

- Multicollinearity & Feature Selection

Missing Values

The number of missing values in the data was extremely low, so instead of imputing those values, I just remove those rows.

# remove rows where values are missing

data_for_model.isna().sum()

data_for_model.dropna(how = "any", inplace = True)

Outliers

Because Linear Regression models can be sensitive to outliers, I want to know how extreme they are when compared to a normal variance.

The table below is contructed from the output of:

data_for_model.describe()

| metric | distance_from_store | credit_score | total_sales | total_items | transaction_count | product_area_count | average_basket_value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | 2.02 | 0.60 | 1846.50 | 278.30 | 44.93 | 4.31 | 36.78 |

| std | 2.57 | 0.10 | 1767.83 | 214.24 | 21.25 | 0.73 | 19.34 |

| min | 0.00 | 0.26 | 45.95 | 10.00 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 9.34 |

| 25% | 0.71 | 0.53 | 942.07 | 201.00 | 41.00 | 4.00 | 22.41 |

| 50% | 1.65 | 0.59 | 1471.49 | 258.50 | 50.00 | 4.00 | 30.37 |

| 75% | 2.91 | 0.66 | 2104.73 | 318.50 | 53.00 | 5.00 | 47.21 |

| max | 44.37 | 0.88 | 9878.76 | 1187.00 | 109.00 | 5.00 | 102.34 |

Here, the max values are much higher than the median value in the columns distance_from_store, total_sales, and total_items.

For example, the median distance_to_store is 1.645 miles, but the maximum is over 44 miles! and that number is well over twice the 75th percentile (a common treshold to determine outliers).

I’ll remove these outliers using the “boxplot approach”, removing rows where the values within those columns are outside of the interquartile range multiplied by 2.

outlier_columns = ["distance_from_store", "total_sales", "total_items"]

# boxplot approach

for column in outlier_columns:

lower_quartile = data_for_model[column].quantile(0.25)

upper_quartile = data_for_model[column].quantile(0.75)

iqr = upper_quartile - lower_quartile

iqr_extended = iqr * 2

min_border = lower_quartile - iqr_extended

max_border = upper_quartile + iqr_extended

outliers = data_for_model[(data_for_model[column] < min_border) | (data_for_model[column] > max_border)].index

print(f"{len(outliers)} outliers detected in column {column}")

data_for_model.drop(outliers, inplace = True)

Split Out Data For Modelling

Next, the data must be split into an X object which contains only the predictor variables, and a y object that contains only the dependent variable.

Then, the data is split into training and test sets, using 80% of the data for training, and the remaining 20% for validation.

# split data into X and y objects for modelling

X = data_for_model.drop(["customer_loyalty_score"], axis = 1)

y = data_for_model["customer_loyalty_score"]

# split out training & test sets

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size = 0.2, random_state = 42)

Categorical Predictor Variables

In the dataset, there is one categorical variable gender which has values of “M” for Male, “F” for Female (the missing values have already been removed).

For the Linear Regression model, all of the variables have to take on a numeric shape, so gender will be recoded to a “dummy” variable, of 0s and 1s. Because there are only two values in the column, we simply recode one group (M) = 1 and the other (F) = 0. For variables with multiple nominal categories, we would need to add additional columns, while withholding one category as a reference group. The output will be interpreted as the effect of being Male (i.e., relative to being female).

Although there are only two categories in this particular case (i.e., we could have manually recoded before splitting the data), the One_Hot_Encoder function in Python’s scikitlearn package can do this in a way that: a) is consistent and compatible with other skikitlearn functions, b) that provides a template for future recoding, c) can automatically handle a more complex data, for example, if/when ‘non-binary’ categories appear in the gender column, and d) which allows for pipeline compatibility for future, unknown data.

After recoding, I turn the training and test objects back into Pandas Dataframes, with the column names applied.

# list of categorical variables that need encoding

categorical_vars = ["gender"]

# instantiate OHE class

one_hot_encoder = OneHotEncoder(sparse_output=False, drop = "first")

# apply OHE

X_train_encoded = one_hot_encoder.fit_transform(X_train[categorical_vars])

X_test_encoded = one_hot_encoder.transform(X_test[categorical_vars])

# extract feature names for encoded columns

encoder_feature_names = one_hot_encoder.get_feature_names_out(categorical_vars)

# turn objects back to pandas dataframe

X_train_encoded = pd.DataFrame(X_train_encoded, columns = encoder_feature_names)

X_train = pd.concat([X_train.reset_index(drop=True), X_train_encoded.reset_index(drop=True)], axis = 1)

X_train.drop(categorical_vars, axis = 1, inplace = True)

X_test_encoded = pd.DataFrame(X_test_encoded, columns = encoder_feature_names)

X_test = pd.concat([X_test.reset_index(drop=True), X_test_encoded.reset_index(drop=True)], axis = 1)

X_test.drop(categorical_vars, axis = 1, inplace = True)

Feature Selection

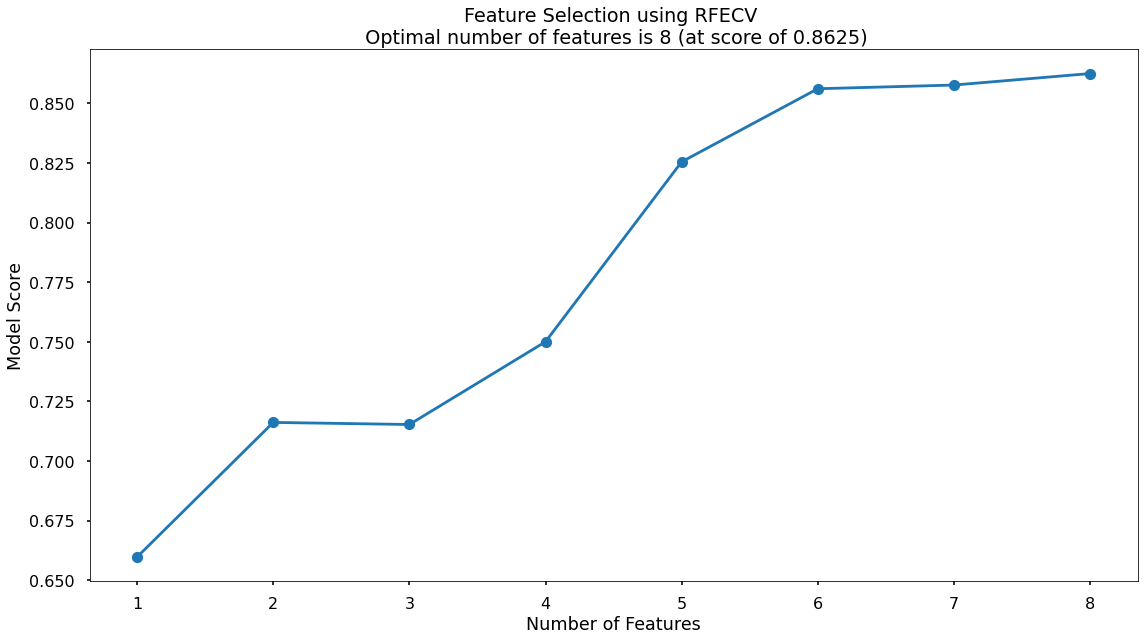

In our data, we are only dealing with eight independent variables, and because prediction accuracy is our goal, we might safely test all of our models with all inputs. But Feature Selection should be included as a matter of methodological rigor. Feature Selection can help us improve model accuracy if there is “noise” and/or multicolinearity among input variables. For Big Data analysis, selecting the right features can also help train models more efficiently. But my favorite reason is that Feature Selection helps us to interpret and explain what models are doing. Although in this project we’re aiming for predictive accuracy over parsimony, at a human level it is easier to tell stories with data one variable at a time.

Recursive Feature Elimination With Cross Validation (RFECV) is a feature selection algorithm that starts with all input variables in a model, and then iteratively removes those with the weakest relationships to the output variable. To cross-validate, it then splits the data into many “chunks” and iteratively trains & validates models on each “chunk” seperately. This means that each time we assess different models with different variables included, or eliminated, the algorithm also knows how accurate each of those models are. From the suite of model scenarios that are created, the algorithm can determine which provided the best accuracy, and thus can infer the best set of input variables to use! RFECV is easily carried out using scikitlearn, and follows the same coding structure as other functions, so for all that is going on under the hood, it is rather convienient and easy to use.

# instantiate RFECV & the model type to be utilised

regressor = LinearRegression()

feature_selector = RFECV(regressor)

# fit RFECV onto our training & test data

fit = feature_selector.fit(X_train,y_train)

# extract & print the optimal number of features

optimal_feature_count = feature_selector.n_features_

print(f"Optimal number of features: {optimal_feature_count}")

# limit our training & test sets to only include the selected variables

X_train = X_train.loc[:, feature_selector.get_support()]

X_test = X_test.loc[:, feature_selector.get_support()]

The below code then produces a plot to visualize the cross-validated accuracy with each potential number of features.

plt.style.use('seaborn-v0_8-poster')

plt.plot(range(1, len(fit.cv_results_['mean_test_score']) + 1), fit.cv_results_['mean_test_score'], marker = "o")

plt.ylabel("Model Score")

plt.xlabel("Number of Features")

plt.title(f"Feature Selection using RFE \n Optimal number of features is {optimal_feature_count} (at score of {round(max(fit.cv_results_['mean_test_score']),4)})")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

So, according to the algorithm, the highest cross-validated accuracy (0.8635) is actually when all eight of our original input variables are included. This is marginally higher than 6 included variables, and 7 included variables. Again, because our goal is prediction over interpretation, we’ll use all 8!

Model Training

Instantiating and training the Linear Regression model is done using the below code

# instantiate the model object

regressor = LinearRegression()

# fit the model using our training & test sets

regressor.fit(X_train, y_train)

Model Performance Assessment

Predict On The Test Set

To assess how well the model is predicting on new data - use the trained model object (regressor) and ask it to predict the loyalty_score variable for the test set.

# predict on the test set

y_pred = regressor.predict(X_test)

Calculate R-Squared

R-Squared is the proportion of variance explained (PVE) metric for regression models. It ranges from 0 to 1, and it can be interpretted as the percentage of variance in our output variable y that is being explained by our input variable(s) x. For example, If the r-squared score was 0.8, 80% of the variation of our output variable is being explained by the input variables - and something else, or some other variables must account for the other 20%.

To calculate r-squared, use scikitlearns’s r_squared function and pass in our predicted outputs for the test set (y_pred), as well as the actual outputs for the test set (y_test).

# calculate r-squared for our test set predictions

r_squared = r2_score(y_test, y_pred)

print(r_squared)

The resulting r-squared score from this is 0.78

Calculate Cross Validated R-Squared

An even more powerful and reliable way to assess model performance is to use Cross Validation.

Instead of simply dividing the data into a single training set, and a single test set, Cross Validation breaks the data into a number of splits and then iteratively train the model on all but one of the splits, test the model on the remaining split until each has had a chance to be the test set.

The result is a number of test set validation results - depending on how many splits we divide the data into - and we can take the average of these to give a much more robust & reliable view of how the model will perform on new, un-seen data!

In the code below, I specify 4 splits and then pass in the regressor object, the training set, and the test set.

Finally, we take the mean of all four test set results.

# calculate the mean cross validated r-squared for our test set predictions

cv = KFold(n_splits = 4, shuffle = True, random_state = 42)

cv_scores = cross_val_score(regressor, X_train, y_train, cv = cv, scoring = "r2")

cv_scores.mean()

The mean cross-validated r-squared score from this is 0.853

Calculate Adjusted R-Squared

When applying Linear Regression with multiple input variables, the r-squared metric on it’s own can end up being an overinflated view of goodness of fit because each input variable will have an additive effect on the overall r-squared score. In other words, every input variable added to the model increases the r-squared value, and never decreases it, even if the relationship is by chance.

Adjusted R-Squared is a metric that compensates for the addition of input variables, and only increases if the variable improves the model above what would be obtained by probability. It is best practice to use Adjusted R-Squared when assessing the results of a Linear Regression with multiple input variables, as it gives a fairer perception the fit of the data.

# calculate adjusted r-squared for our test set predictions

num_data_points, num_input_vars = X_test.shape

adjusted_r_squared = 1 - (1 - r_squared) * (num_data_points - 1) / (num_data_points - num_input_vars - 1)

print(adjusted_r_squared)

The resulting adjusted r-squared score from this is 0.754 which as expected, is slightly lower than the score we got for r-squared on it’s own.

Model Summary Statistics

Although our overall goal for this project is predictive accuracy, rather than an explcit understanding of the relationships of each of the input variables and the output variable, it is always interesting to look at the summary statistics for these.

# extract model coefficients

coefficients = pd.DataFrame(regressor.coef_)

input_variable_names = pd.DataFrame(X_train.columns)

summary_stats = pd.concat([input_variable_names,coefficients], axis = 1)

summary_stats.columns = ["input_variable", "coefficient"]

# extract model intercept

regressor.intercept_

Unfortunately, because scikitlearn’s functionality is focused on prediction rather than inference, the regressor object does not store p-values or t-statistics. To get those, we can use the OLS function in the statsmodels package, which also returns the coefficients and intercept, above.

import statsmodels.api as sm

X_train = X_train.reset_index(drop=True)

y_train = y_train.reset_index(drop=True)

X_train_sm = sm.add_constant(X_train)

model = sm.OLS(y_train, X_train_sm).fit()

print(model.summary())

The information from that code block can be found in the table below:

| input_variable | coefficient | p-value, * < 0.05, ** < 0.01 |

|---|---|---|

| intercept | 0.516 | ** |

| distance_from_store | -0.201 | ** |

| credit_score | -0.028 | |

| total_sales | 0.000 | ** |

| total_items | 0.001 | ** |

| transaction_count | -0.005 | ** |

| product_area_count | 0.062 | ** |

| average_basket_value | -0.004 | |

| gender_M | -0.013 |

Again, because the objective here is prediction rather than interpretation, I will try not to digress too far here. However, we can use these coefficients, in conjunction with the p-values, to interpret how the model is making its predictions. Although not shown here, distance_from_store has the lowest p-value, and the furthest t-statistic, which flags it as the most significant predictor variable.

The distance_from_store coefficient value of -0.201 tells us that loyalty_score decreases by 0.201 (or 20% as loyalty score is a percentage) for every additional mile that a customer lives from the store. This makes intuitive sense, as customers who live a long way from this store, most likely live near another store where they might do some of their shopping as well, whereas customers who live near this store, probably do a greater proportion of their shopping at this store…and hence have a higher loyalty score.

Other variables such as total items and total sales are statistically significant, but their actual effects appear small. For example, it appears that loyalty score improves by only a tenth of a percent for each additional item a customer purchases. On the other hand, although the model returns a coefficient for gender, it is not statistically significant, and thus the effect of being in the “M” category is meaningless.

Decision Tree

Next, I’ll use the scikit-learn library in Python to model the data using a Decision Tree. Decision Trees work by splitting the predictor variables into branches according to how well they explain the dependent variable, and it continues to split each branch until it has predicted every value of the depenent variable, or until it is told to stop. If some of the input variables are not linearly related to the output, but may be related in a “U-shaped” curve, for example, then the decision tree will pick up on this type of relationship whereas a Linear Regression model will not. On the other hand, if all of the input are normally distributed and linearly related, then a Decision Tree would only approximate the linear relationship, and it would be less precise. We will know if it is more or less effective by comparing the adjusted R-squared metric for this and other models.

The Decision Tree code is organized in the same 4 key sections:

- Data Import

- Data Preprocessing

- Model Training

- Performance Assessment

Data Import

Same as in the Linear Regression model, above, I import the pickel file, remove the id column, and shuffle the data. The only difference here is the use of scikitlearn’s Decision Tree functionality.

# import required packages

import pandas as pd

import pickle

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeRegressor, plot_tree

from sklearn.utils import shuffle

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split, cross_val_score, KFold

from sklearn.metrics import r2_score

from sklearn.preprocessing import OneHotEncoder

# import modelling data

data_for_model = pickle.load(open("data/customer_loyalty_modelling.p", "rb"))

# drop uneccessary columns

data_for_model.drop("customer_id", axis = 1, inplace = True)

# shuffle data

data_for_model = shuffle(data_for_model, random_state = 42)

Data Preprocessing

While Linear Regression is susceptible to the effects of outliers, and highly correlated input variables - Decision Trees are not, so the required preprocessing here is lighter. The logic of the steps below is the same as the above for Linear Regression, so my comments are limited.

Missing Values

# remove rows where values are missing

data_for_model.isna().sum()

data_for_model.dropna(how = "any", inplace = True)

Split Out Data For Modelling

# split data into X and y objects for modelling

X = data_for_model.drop(["customer_loyalty_score"], axis = 1)

y = data_for_model["customer_loyalty_score"]

# split out training & test sets

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size = 0.2, random_state = 42)

Categorical Predictor Variables

# list of categorical variables that need encoding

categorical_vars = ["gender"]

# instantiate OHE class

one_hot_encoder = OneHotEncoder(sparse=False, drop = "first")

# apply OHE

X_train_encoded = one_hot_encoder.fit_transform(X_train[categorical_vars])

X_test_encoded = one_hot_encoder.transform(X_test[categorical_vars])

# extract feature names for encoded columns

encoder_feature_names = one_hot_encoder.get_feature_names_out(categorical_vars)

# turn objects back to pandas dataframe

X_train_encoded = pd.DataFrame(X_train_encoded, columns = encoder_feature_names)

X_train = pd.concat([X_train.reset_index(drop=True), X_train_encoded.reset_index(drop=True)], axis = 1)

X_train.drop(categorical_vars, axis = 1, inplace = True)

X_test_encoded = pd.DataFrame(X_test_encoded, columns = encoder_feature_names)

X_test = pd.concat([X_test.reset_index(drop=True), X_test_encoded.reset_index(drop=True)], axis = 1)

X_test.drop(categorical_vars, axis = 1, inplace = True)

Model Training

Instantiating and training the Decision Tree model is done using the below code. The random_state parameter ensures that the results are reproducible, and this helps to understand any improvements in performance with changes to model hyperparameters.

# instantiate our model object

regressor = DecisionTreeRegressor(random_state = 42)

# fit our model using our training & test sets

regressor.fit(X_train, y_train)

Model Performance Assessment

Predict On The Test Set

# predict on the test set

y_pred = regressor.predict(X_test)

Calculate R-Squared

# calculate r-squared for our test set predictions

r_squared = r2_score(y_test, y_pred)

print(r_squared)

The resulting r-squared score from this is 0.898

Calculate Cross Validated R-Squared

As with the Linear Regression, we can again cross validate the results by splitting the data into different training and test sets, training and testing the model “k” times, deriving “k” r-squared scores, and then taking the mean of the results.

# calculate the mean cross validated r-squared for our test set predictions

cv = KFold(n_splits = 4, shuffle = True, random_state = 42)

cv_scores = cross_val_score(regressor, X_train, y_train, cv = cv, scoring = "r2")

cv_scores.mean()

The mean cross-validated r-squared score from this is 0.871 which is slighter higher than we saw for Linear Regression.

Calculate Adjusted R-Squared

# calculate adjusted r-squared for our test set predictions

num_data_points, num_input_vars = X_test.shape

adjusted_r_squared = 1 - (1 - r_squared) * (num_data_points - 1) / (num_data_points - num_input_vars - 1)

print(adjusted_r_squared)

The resulting adjusted r-squared score from this is 0.887 which as expected, is slightly lower than the score we got for r-squared on it’s own.

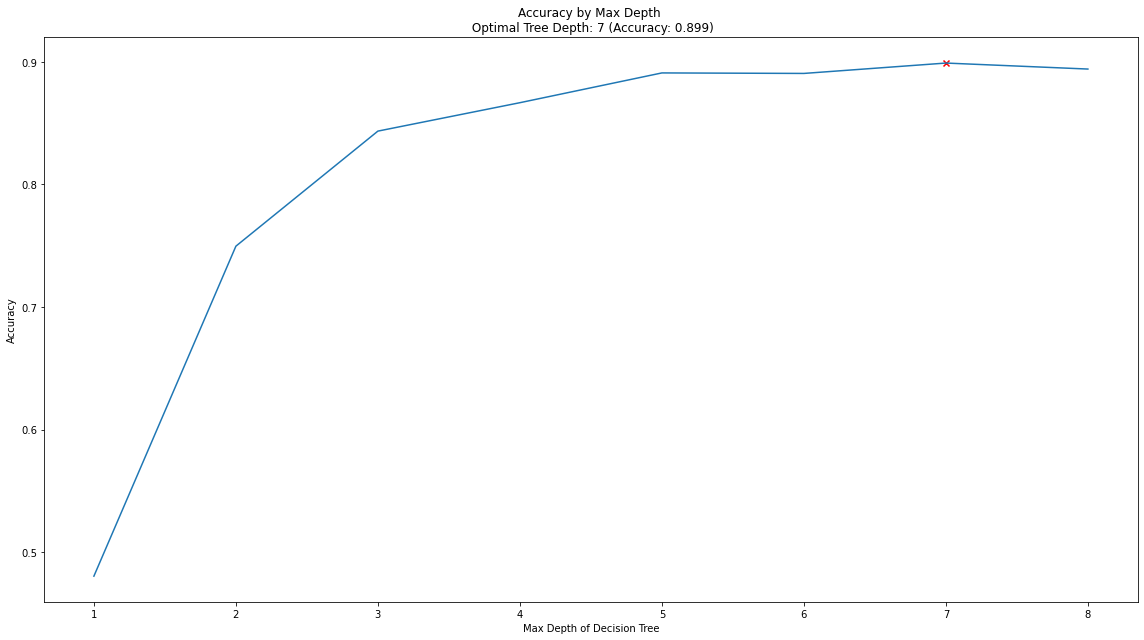

Decision Tree Regularization

Another drawback of Decision Trees is that they can “over-fit”. Unless the algorithm is given some limiting parameters, it will exhaust all possible splits in the data until it has explained every case of the dependent variable. But it if learns the training data too well, it might not be able to handle real-world, unseen data. It is better to have a model that is more flexible and can make effective generalizations about unseen data.

One effective method of avoiding this over-fitting, is to apply a max depth parameter to the Decision Tree, meaning we only allow it to split the data a certain number of times before it is required to stop.

Where to set the maximum depth, however, is not obvious. One method, shown below, loops over a variety of max-depth values, runs the model with each max depth, and assesses which gives us the best predictive performance!

# finding the best max_depth

# set up range for search, and empty list to append accuracy scores to

max_depth_list = list(range(1,9))

accuracy_scores = []

# loop through each possible depth, train and validate model, append test set accuracy

for depth in max_depth_list:

regressor = DecisionTreeRegressor(max_depth = depth, random_state = 42)

regressor.fit(X_train,y_train)

y_pred = regressor.predict(X_test)

accuracy = r2_score(y_test,y_pred)

accuracy_scores.append(accuracy)

# store max accuracy, and optimal depth

max_accuracy = max(accuracy_scores)

max_accuracy_idx = accuracy_scores.index(max_accuracy)

optimal_depth = max_depth_list[max_accuracy_idx]

Now we can visualize this max depth test.

# plot accuracy by max depth

plt.plot(max_depth_list,accuracy_scores)

plt.scatter(optimal_depth, max_accuracy, marker = "x", color = "red")

plt.title(f"Accuracy by Max Depth \n Optimal Tree Depth: {optimal_depth} (Accuracy: {round(max_accuracy,4)})")

plt.xlabel("Max Depth of Decision Tree")

plt.ylabel("Accuracy")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

In the plot we can see that the maximum classification accuracy on the test set is found when applying a max_depth value of 7. However, we lose very little accuracy back to a value of 4, but this would result in a simpler model, that generalizes even better on new data. We make the executive decision to re-train our Decision Tree with a maximum depth of 4.

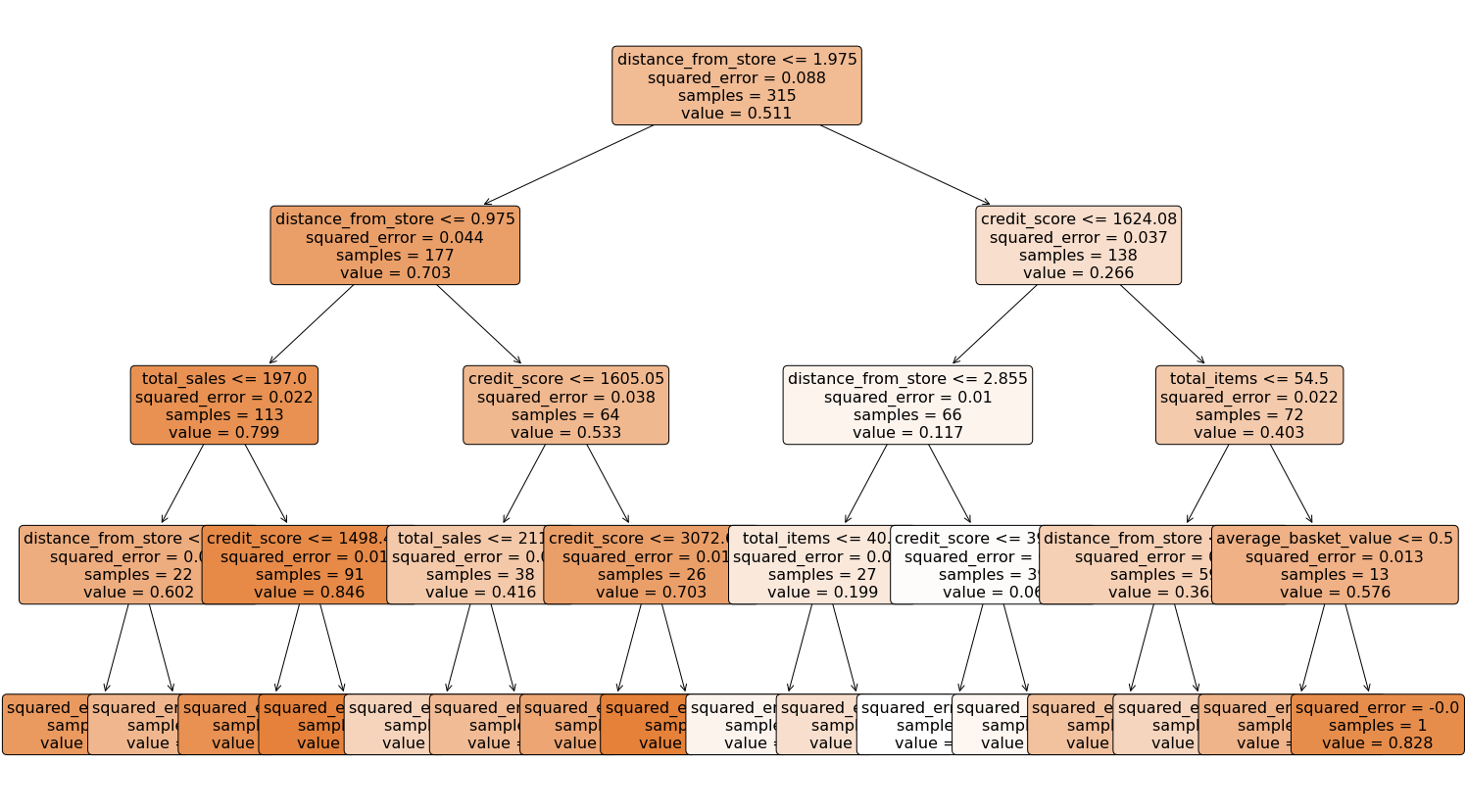

Visualize Our Decision Tree

To see the decisions that have been made in the (re-fitted) tree, we can use the plot_tree functionality that we imported from scikit-learn.

# re-fit our model using max depth of 4

regressor = DecisionTreeRegressor(random_state = 42, max_depth = 4)

regressor.fit(X_train, y_train)

# plot the nodes of the decision tree

plt.figure(figsize=(25,15))

tree = plot_tree(regressor,

feature_names = X.columns,

filled = True,

rounded = True,

fontsize = 16)

That code gives us the below plot:

This is a very powerful visual that helps us interpret what the model is doing ‘under the hood’, which can be useful for stakeholders. Like in the Linear Regression Model’s coefficient output, we can interpret the model’s predictions, but here the findings are even more intuitive. For example, most of the variance in customer loyalty can be found by splitting the data between those who live less than or equal to 1.975 miles from the store.

___

Random Forest

Finally, I’ll use the scikit-learn library in Python to model the data using a Random Forest. Random Forest models are ensembles of many decision trees, in which the data are randomized and limited from tree to tree, thereby forcing each tree in the forest to make a slightly different prediction. The algorithm then finds a consensus among the trees to make decisions and how and where to split the data.

The code sections below are broken up into 4 key sections:

- Data Import

- Data Preprocessing

- Model Training

- Performance Assessment

Again, because the logic is similar from section to section, my comments are truncated for brevity.

Data Import

# import required packages

import pandas as pd

import pickle

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestRegressor

from sklearn.utils import shuffle

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split, cross_val_score, KFold

from sklearn.metrics import r2_score

from sklearn.preprocessing import OneHotEncoder

from sklearn.inspection import permutation_importance

# import modelling data

data_for_model = pickle.load(open("data/customer_loyalty_modelling.p", "rb"))

# drop uneccessary columns

data_for_model.drop("customer_id", axis = 1, inplace = True)

# shuffle data

data_for_model = shuffle(data_for_model, random_state = 42)

Data Preprocessing

Random Forests, just like Decision Trees, are not influenced by outliers, so the required preprocessing here is lighter.

- Missing values in the data

- Encoding categorical variables to numeric form

Missing Values

# remove rows where values are missing

data_for_model.isna().sum()

data_for_model.dropna(how = "any", inplace = True)

Split Out Data For Modelling

# split data into X and y objects for modelling

X = data_for_model.drop(["customer_loyalty_score"], axis = 1)

y = data_for_model["customer_loyalty_score"]

# split out training & test sets

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size = 0.2, random_state = 42)

Categorical Predictor Variables

# list of categorical variables that need encoding

categorical_vars = ["gender"]

# instantiate OHE class

one_hot_encoder = OneHotEncoder(sparse=False, drop = "first")

# apply OHE

X_train_encoded = one_hot_encoder.fit_transform(X_train[categorical_vars])

X_test_encoded = one_hot_encoder.transform(X_test[categorical_vars])

# extract feature names for encoded columns

encoder_feature_names = one_hot_encoder.get_feature_names_out(categorical_vars)

# turn objects back to pandas dataframe

X_train_encoded = pd.DataFrame(X_train_encoded, columns = encoder_feature_names)

X_train = pd.concat([X_train.reset_index(drop=True), X_train_encoded.reset_index(drop=True)], axis = 1)

X_train.drop(categorical_vars, axis = 1, inplace = True)

X_test_encoded = pd.DataFrame(X_test_encoded, columns = encoder_feature_names)

X_test = pd.concat([X_test.reset_index(drop=True), X_test_encoded.reset_index(drop=True)], axis = 1)

X_test.drop(categorical_vars, axis = 1, inplace = True)

Model Training

Instantiating and training our Random Forest model is done using the below code.

Other than setting the random_state to the familiar 42, all other parameters are set to their default values. Among other things, this means that our forest will be built from 100 Decision Trees.

# instantiate our model object

regressor = RandomForestRegressor(random_state = 42)

# fit our model using our training & test sets

regressor.fit(X_train, y_train)

Model Performance Assessment

Predict On The Test Set

# predict on the test set

y_pred = regressor.predict(X_test)

Calculate R-Squared

# calculate r-squared for our test set predictions

r_squared = r2_score(y_test, y_pred)

print(r_squared)

The resulting r-squared score from this is 0.957 - higher than both Linear Regression & the Decision Tree.

Calculate Cross Validated R-Squared

# calculate the mean cross validated r-squared for our test set predictions

cv = KFold(n_splits = 4, shuffle = True, random_state = 42)

cv_scores = cross_val_score(regressor, X_train, y_train, cv = cv, scoring = "r2")

cv_scores.mean()

The mean cross-validated r-squared score from this is 0.923 which agian is higher than we saw for both Linear Regression & our Decision Tree.

Calculate Adjusted R-Squared

# calculate adjusted r-squared for our test set predictions

num_data_points, num_input_vars = X_test.shape

adjusted_r_squared = 1 - (1 - r_squared) * (num_data_points - 1) / (num_data_points - num_input_vars - 1)

print(adjusted_r_squared)

The resulting adjusted r-squared score from this is 0.955 which as expected, is slightly lower than the score we got for r-squared on it’s own - but again higher than for our other models.

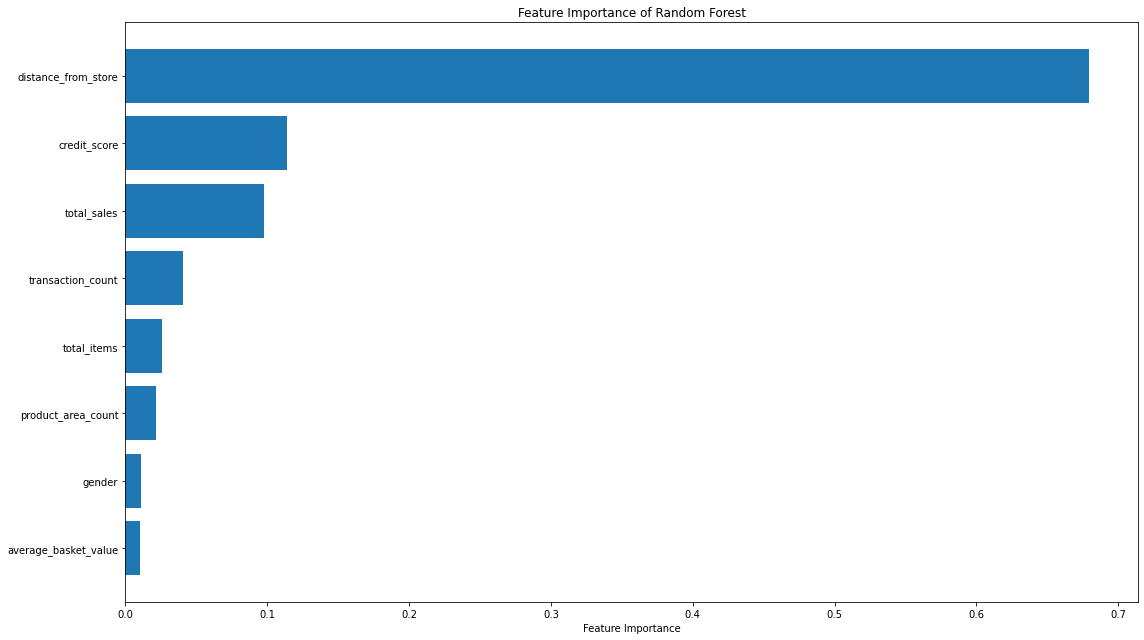

Feature Importance

In the Linear Regression model, to understand the relationships between input variables and our ouput variable, loyalty score, we examined the coefficients. With our Decision Tree we looked at what the earlier splits were. These allowed us some insight into which input variables were having the most impact.

Because Random Forests are an ensemble of many Decision Trees, we end up with a powerful and robust model, but because of the random or different nature of all these Decision trees - the model gives us a unique insight into how important each of our input variables are to the overall model.

So, in a Random Forest the importance of a feature is measured by asking How much would accuracy decrease if a specific input variable was removed or randomized?

If this decrease in accuracy is large, then we’d deem that input variable to be quite important, and if there is only a small decrease in accuracy, then we’d conclude that the variable is of less importance.

There are a couple ways to go about this: Feature Importance, and Permutation Importance

Feature Importance is where we find all nodes in the Decision Trees of the forest where a particular input variable is used to split the data and assess what the Mean Squared Error (for a Regression problem) was before the split was made, and compare this to the Mean Squared Error after the split was made. We can take the average of these improvements across all Decision Trees in the Random Forest to get a score that tells us how much better we’re making the model by using that input variable. If we do this for each of our input variables, we can compare these scores and understand which is adding the most value to the predictive power of the model!

Permutation Importance uses the data that has gone unused when the random samples are selected for each Decision Tree (each tree is “bootstrapped” from the training set, meaning it is sampled with replacement, so there will always be unused data in each tree. This unused data (i.e., not randomly selected) is known as Out of Bag observations and these can be used for testing the accuracy of each particular Decision Tree. For each Decision Tree, the Out of Bag observations are gathered and then passed through the same Tree models as if they were a second test set, and we can obtain an accuracy score, R-squared. Then, in order to understand the importance of a feature, we randomize the values within one of the input variables - a process that essentially destroys any relationship that might exist between that input variable and the output variable - and run that updated data through the Decision Tree again, obtaining a second accuracy score. The difference between the original accuracy and the new accuracy gives us a view on how important that particular variable is for predicting the output.

Permutation Importance is often preferred over Feature Importance which can at times inflate the importance of numerical features. Both are useful, and in most cases will give fairly similar results.

Let’s put them both in place, and plot the results…

# calculate feature importance

feature_importance = pd.DataFrame(regressor.feature_importances_)

feature_names = pd.DataFrame(X.columns)

feature_importance_summary = pd.concat([feature_names,feature_importance], axis = 1)

feature_importance_summary.columns = ["input_variable","feature_importance"]

feature_importance_summary.sort_values(by = "feature_importance", inplace = True)

# plot feature importance

plt.barh(feature_importance_summary["input_variable"],feature_importance_summary["feature_importance"])

plt.title("Feature Importance of Random Forest")

plt.xlabel("Feature Importance")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

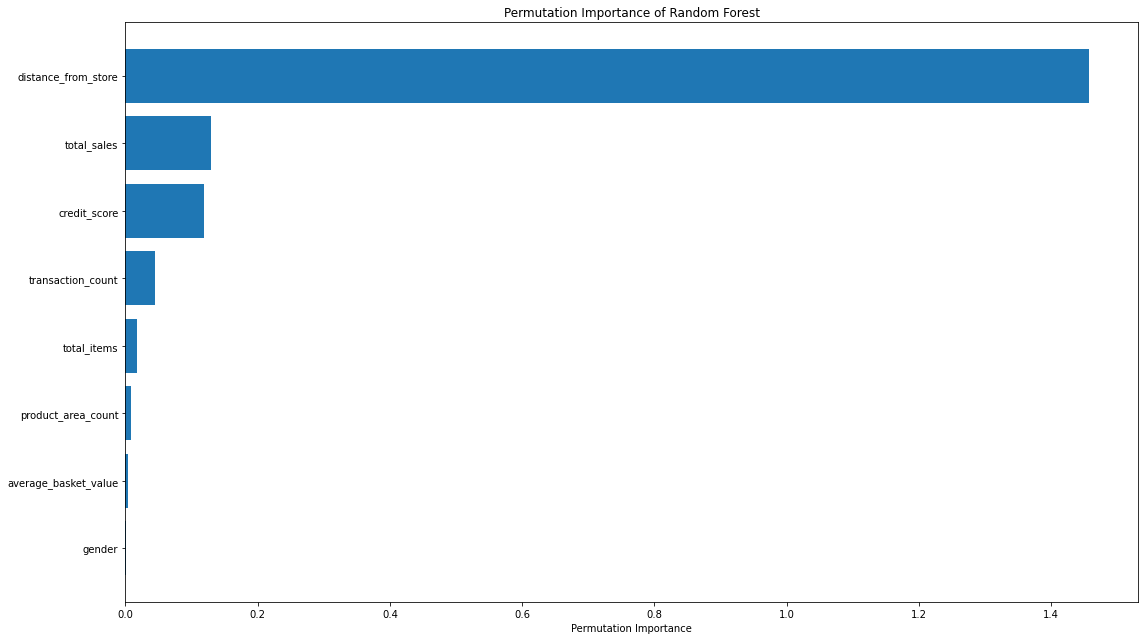

# calculate permutation importance

result = permutation_importance(regressor, X_test, y_test, n_repeats = 10, random_state = 42)

permutation_importance = pd.DataFrame(result["importances_mean"])

feature_names = pd.DataFrame(X.columns)

permutation_importance_summary = pd.concat([feature_names,permutation_importance], axis = 1)

permutation_importance_summary.columns = ["input_variable","permutation_importance"]

permutation_importance_summary.sort_values(by = "permutation_importance", inplace = True)

# plot permutation importance

plt.barh(permutation_importance_summary["input_variable"],permutation_importance_summary["permutation_importance"])

plt.title("Permutation Importance of Random Forest")

plt.xlabel("Permutation Importance")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

That code gives us the below plots - the first being for Feature Importance and the second for Permutation Importance.

The overall story from both approaches is very similar, in that by far, the most important or impactful input variable is distance_from_store which is the same insights we derived when assessing our Linear Regression & Decision Tree models.

There are slight differences in the order or “importance” for the remaining variables but overall they have provided similar findings.

___

Modelling Summary

The most important outcome for this project was predictive accuracy, rather than explicitly understanding the drivers of prediction. Based upon this, we chose the model that performed the best when predicted on the test set - the Random Forest.

Metric 1: Adjusted R-Squared (Test Set)

- Random Forest = 0.955

- Decision Tree = 0.886

- Linear Regression = 0.754

Metric 2: R-Squared (K-Fold Cross Validation, k = 4)

- Random Forest = 0.925

- Decision Tree = 0.871

- Linear Regression = 0.853

Even though we were not specifically interested in the drivers of prediction, it was interesting to see across all three modelling approaches, that the input variable with the biggest impact on the prediction was distance_from_store rather than variables such as total sales. This is interesting information for the business, so discovering this as we went was worthwhile. As noted above, more value may be created by getting some more detailed geographic information about customers, as well as where nearby stores are located.

Predicting Missing Loyalty Scores

We have selected the model to use (Random Forest) and now we need to make the loyalty_score predictions for those customers that the market research consultancy were unable to tag.

We cannot just pass the data for these customers into the model, as is - we need to ensure the data is in exactly the same format as what was used when training the model.

In the following code, we will

- Import the required packages for preprocessing

- Import the data for those customers who are missing a loyalty_score value

- Import our model object & any preprocessing artifacts

- Drop columns that were not used when training the model (customer_id)

- Drop rows with missing values

- Apply One Hot Encoding to the gender column (using transform)

- Make the predictions using .predict()

# import required packages

import pandas as pd

import pickle

# import customers for scoring

to_be_scored = ...

# import model and model objects

regressor = ...

one_hot_encoder = ...

# drop unused columns

to_be_scored.drop(["customer_id"], axis = 1, inplace = True)

# drop missing values

to_be_scored.dropna(how = "any", inplace = True)

# apply one hot encoding (transform only)

categorical_vars = ["gender"]

encoder_vars_array = one_hot_encoder.transform(to_be_scored[categorical_vars])

encoder_feature_names = one_hot_encoder.get_feature_names(categorical_vars)

encoder_vars_df = pd.DataFrame(encoder_vars_array, columns = encoder_feature_names)

to_be_scored = pd.concat([to_be_scored.reset_index(drop=True), encoder_vars_df.reset_index(drop=True)], axis = 1)

to_be_scored.drop(categorical_vars, axis = 1, inplace = True)

# make our predictions!

loyalty_predictions = regressor.predict(to_be_scored)

No we have our loyalty_score predictions for these missing customers. Due to the impressive metrics on the test set, we can be reasonably confident with these scores. This extra customer information will ensure our client can undertake more accurate and relevant customer tracking, targeting, and comms.

Growth & Next Steps

While predictive accuracy was relatively high, we could continue to search for more predictive power, perhaps by:

- using other modelling approaches, for example XGBoost, LightGBM,

- tuning the hyperparameters of the Random Forest, such as tree depth, as well as potentially training on a higher number of Decision Trees in the Random Forest.

Or, from a data point of view, further variables could be collected, and further feature engineering could be undertaken to ensure that we have as much useful information available for predicting customer loyalty. Since we have looked “under the hood” of each of our models and found that distance_from_store is the most powerful predictor, more value may be created by getting some more detailed geographic information about customers, as well as where nearby stores are located.